Every American should make it a point to see “The Big Short”…

That was the first sentiment expressed by a close friend of mine when I told her that I finally sat down and watched it this past week, and one that I wholeheartedly agreed with. Not only was it a film that I enjoyed far more then I thought I would, it was also one that for what it’s worth I was downright impressed with. If years ago while watching “Anchorman”, “Talledega Nights”, or “Step Brothers” you would have told me that the director of these films would later go on to direct a largely serious, yet easy to digest take on the credit/housing bubble collapse of 2008 I’m not sure if I would have believed you.

Adam McKay did just this with 2015’s “The Big Short”, a film that earned him an Oscar win for “Best Adapted Screenplay”, and one which will undoubtedly give him the option to move his career into realms outside of the ones that feature Will Farrell playing some form of hilariously overbearing man-child, (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

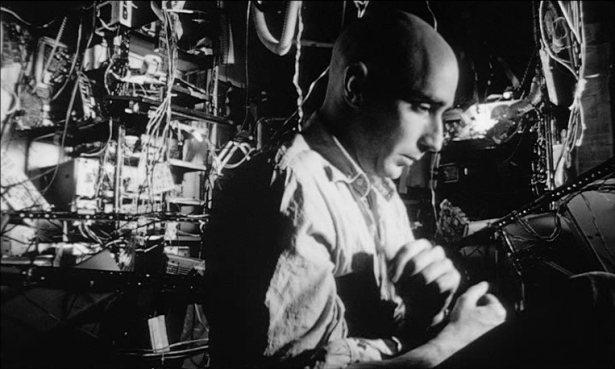

At first glance I was ready to chalk up “The Big Short’s” cinematography as “workman-like”, no doubt beautifully executed but still nothing flashy. Certainly the way it should have been in order to best serve the story it’s trying to tell. However, it wasn’t long into the film’s 130 minute run time that I began to notice that there was more going on beneath the surface with Director of Photography Barry Ackroyd’s visuals then I initially thought. In this case it had less to do with the lighting and more to do with the camera work, and is fairly well represented in the scene below…

to call Ackroyd’s camerawork “frenetic” at times may be an overstatement, though it isn’t far off the mark. Handheld camera aesthetics are commonplace in cinema created at every budget level, but pulling it off so that isn’t over done to the point of annoyance can be a difficult line to walk. Throughout the entirety of “The Big Short” the camera is on the move to the point at which it would be accurate, (if not a little cliche) to say that the camera itself becomes a character in its own right.

I’m of the opinion that McKay and his team were successful in the implementation of their moving camera, managing to not overwhelm the proceedings with its presence. In my viewing experience the roving camera adds an energy to a narrative that is largely conversation over action. It effectively brings the audience into this high stakes world, dropping us into the offices and conference rooms right along side the other characters.

Ever drifting, panning, and refocusing, the camera serves as our eyes – always shifting viewpoints in an effort to keep up with the information that we are becoming privy to, as well as to the plans that are being unhatched. By the end of the film the audience can’t help but to feel as if they’ve been right there with the characters all along. We’re a silent partner in their same schemes; an accomplish in their less then above boards gains.

The last scenes leave us with Steve Carell’s Mark Baum, (arguably the most sympathetic of the bunch) left depressed and despondent once the realization of just what has just happened to his industry and the millions it affects. All at once we can’t help feeling the same rage at the machine that he does, while at the same time trying not to admit to ourselves that in a way we could all be more then a little complicit in what’s come to pass.

Chris Magdalenski is a cinematographer and visual designer currently working in NYC. View demo reel here – https://vimeo.com/152823877